THE CANADIAN PANORAMA

By: Alan Hardiman

Lighting & Sound America – October 2015 Issue

With a spectacular fusion of music, dance, acrobatics, aerialists, BMX stunt cyclists, lighting, video, and pyrotechnics that spanned close to three hours, Montreal’s Cirque du Soleil kicked off the 17th Pan American Games in Toronto with an opening ceremony like none other before it. More than two years in the making, the July 10 show—the largest event the Cirque has ever produced—inaugurated the largest Pan Am Games in history, with 6,200 athletes from 41 countries participating in 36 sports.

The show’s broad theme was the coming of age of Canada as a nation, sketched in parallel with the maturation of an individual from childhood to adulthood, all of it overseen by five gods representing the original Olympic Pentathlon, the guardians of javelin, long jump, wrestling, discus, and running.

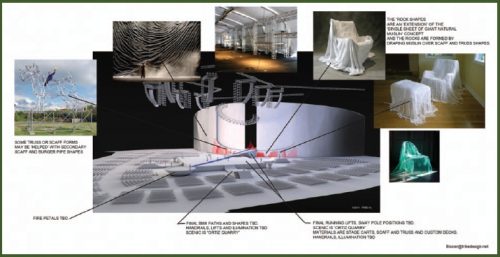

Bruce Rodgers’ set design centered on an 85′ x 85′ diamond-shaped stage flanked by four satellite 20′ x 20′ stages on the field of the domed Rogers Stadium, dubbed Pan Am Stadium for the duration of the games. Directly behind the stage, five spaced 22′ x 40′ Strong MDI screens hung side-by-side to form a 126′ x 40′ surface for video artist Johnny Ranger’s stunning projections, which complemented the live action on the stage and high above it, where Cirque du Soleil aerialists held the sold-out stadium audience of 45,000 in thrall for much of the evening.

Throughout, composer Maxim Lepage’s original score underpinned the performances as well as the parade of athletes, for which he composed a different variation for each and every country, reflecting its own unique music while providing continuity to the parade. Lepage maintained a brisk 120bpm tempo to keep the athletes moving and to prevent this slight diversion from the stage show from dragging down the proceedings.

To serve up the score, Marc Laliberté designed a sound system consisting of 120 Meyer MILO elements—15 in each of eight line arrays flown over the stage, supplemented by 36 deck-mounted Meyer 700HP subs and the stadium’s house PA.

Befitting the spectacle, lighting designer Martin Labrecque lit it in dramatic fashion, using several truckloads of instruments, chief among them Philips Vari-Lite units and Clay Paky Sharpy moving beams.

The show was broadcast live to hundreds of millions of households around the globe, with a feed generated from 29 cameras that also served three IMAG screens flown above the aerialist grid and loudspeaker rigging.

THE BEGINNING

The story unfolded through five major set pieces, or tableaux, beginning with the sound of heavy drumming. The program notes relate that “the entire stadium represents the womb, where tradition says indigenous peoples learned drumming from their mothers’ heartbeats. Drumbeats announce the arrival of the all-knowing eagle that comes to deliver a message.” As the eagle transformed into a human Messenger on the projection screens, dancers mounted the steps to the main stage and that same Messenger arose live from the onstage fog as a group of First Nations People ascended to each of the four satellite stages. (MDG supplied the show’s fog and haze machines.)

The notes explain that “the four ancestral nations of the Greater Golden Horseshoe region of Ontario—the Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation, the Métis Nation of Ontario, the Six Nations of the Grand River, and the Huron Wendat Nation—welcome the Messenger, each in their own way. In this first tableau, the PowWow Carnival of cultural diversity, 183 dancers from 21 dance troupes perform traditional and contemporary choreography from many countries.” DJ Shub, formerly a member of the powwow-step band A Tribe Called Red, scratches along with the pre-recorded score.

Rodgers says, “It was so exciting, just the way they work, because every single person at Cirque du Soleil is so highly creative. For me, it was just a question of jumping in and holding on! I’ve got a number of large-scale stadium shows on my resume—I’m well into my 10th consecutive Super Bowl halftime show as we speak—and they said they needed expertise in set design for television and live events, to take their incredible conceptual design and help sculpt it into a form that could be loaded in on budget and on time without losing the essence of the concept. I’ve done a lot of big shows—with Prince, Bruce Springsteen, and Madonna, for example—and I had always dreamed of working with the Cirque.

“They were about a year into their design process, and as they started to crunch the numbers, they realized they had only a fraction of what the budget needed to be,” Rodgers says. “I got invited in as a production designer, to help them identify the essence of what it is they were trying to do, and somehow help them bring it off. Their storyboards were completely out of this world, and profoundly inspiring. It sounds like I’m going overboard, but I’m not. The visuals and the ideas they had would rival any Cirque show that anybody has ever seen, and any opening ceremonies ever staged across the planet.”

The torch’s arrival early in the proceedings provided a focal point for the rest of the show. Via video projection, past winners handed the flame off to the Canadian Olympic sprint gold-medalist Donovan Bailey, whose stunt double, in a scene reminiscent of the Daniel Craig-James Bond segment at the London 2012 Olympics, BASE jumped from the top of the adjacent CN Tower—the tallest freestanding structure in the Western Hemisphere—and then appeared live, descending to the stage in harness, torch in hand, to wild applause. Bailey handed the torch to 15-year-old diver Faith Zacharias, who placed it in a cobra head-shaped receptacle, to await the lighting of the cauldron at the end of the evening.

“The cobra head—that sliver of pyro pipe that came out of the stage—is just about on the pitcher’s mound,” Rodgers explains. “We did a boatload of spatial studies. As a set designer, you’re always kind of ground-based: what’s happening on the floor to allow for the movement of performers, and also to allow for good sightlines, not only up in the tiered seating but down on the main floor as well. And what are the broadcast cameras going to see? You start working with these floor-based calculations, but with Cirque they are heavily in the air, and you’re in a whole different dimension so that you don’t get a lot of time on any other sort of set design, because nobody flies like the Cirque! You’ve got this massive, amazing rigging for the magnificent aerialist flying rig that you have to work around. It was so exciting to look up at what Danny Zen and his team had done technically with the rig overhead.”

Rodgers hung three 26′ x 15′ IMAG screens at a trim height of 111′ above the stage, facing forward and to both sides. “The Rogers Centre is one of the better roof-covered baseball stadiums in North America, so as long as you’re designing near where they play the game of baseball, you know the sight lines are automatically going to be pretty good. But because we’re telling a story, we needed to add IMAG screens all around the upper part of the set design—not very many, just enough to provide a closer picture of some of the little things on the stage way down there,” he says.

“The whole show felt like IMAG in a very cinematic way, especially when seen together with Johnny Ranger’s video, which was so beautiful,” Rodgers says. “He and Martin Labrecque worked so closely together on balance—you really want to be pushing 50fc off those screens, and the iris on the camera wants to be F2.8 or so, and you feel like you’re watching a very rich presentation, not only in the foreground on the stage, but on the screen content in the back. That was one thing we were super worried about. We had to find the magic number for broadcast that might feel a bit strange in a live setting, but we tweaked that little bit of science between camera and lighting and projection, and we found the sweet spot.”

INTERPLAY OF LIVE ACTION WITH VIDEO PROJECTION

To begin the second tableau, The Fire Line, four costumed stilt walkers representing the bear, caribou, woodpecker, and owl, guided 150 children holding illuminated floor lamps “along trails of discovery, bathed in the glow of the aurora borealis” and a pair of lasers, beneath the steady gaze of the live javelin goddess, who had risen to her apotheosis high atop a scissor lift. Aerialists performed above them, suspended in transparent globes and decorated baskets.

In an effective interplay of live action and projected video that initially looked a lot like IMAG, the javelin goddess appeared on stage as a ballerina, while her onscreen counterpart seemed to mimic her movements, occasionally in slow motion. The frightened children crept off the stage as the latter threw the javelin seemingly straight out of the center screen, spitting fire, igniting the pyro pipe, and dividing the main stage straight down the middle with flames extending almost to the torch in the cobra head at the apex of the diamond.

According to the program notes, “This creates a border that marks the end of childhood and marks the first test on the road to adulthood.” The young people reappeared on either side of the fire line as teenagers with lacrosse sticks, and began to challenge each other across the flames.

Eight of the more acrobatic teens leapt and tumbled over the flames, then began playing a stylized game of lacrosse “to resolve their differences, lacrosse being a traditional alternative to going to war.” On-screen, a Bombardier CL- 415 water bomber flew in low, at a realistic sound level and in glorious surround, to extinguish the fire line, bringing this segment to a close.

This interplay between the live action and video projection recurred throughout the entire show, and was a hallmark of the production that made it fascinating to watch.

“The video was one big image of 1,920 pixels high by side-by-side vertically together, with a space of 4′ between 6,017 pixels wide, projected over five HD screens placed them,” Ranger explains. “Each screen was 1080 x 1920, but when we created the final composition, we filled in the gaps in between, so that took us up to 6,017 pixels wide. It was an enormous rendering project: a two-hour program at 6K resolution. From most positions in the stadium, the screens were massive in comparison to the performers, and therefore had a big impact.”

Ranger served as video projection designer, and was on the project full-time since January, working closely with Cirque’s directors to translate their script and narratives into visual concepts. “With my producer, we hired a small team of motion designers and organized the video shoot in March that I then directed,” he says. “We shot in 4K with the Phantom camera, which we used to shoot scenes, characters and effects at between 300 and 900 frames per second for extra slow motion effects.”

The extra slow motion was particularly effective in sequences involving explosions, granular objects, and powders, due to the Vision Research Phantom Flex4K camera’s very high definition. (Phantom cameras are also used in ballistics testing and particle image velocimetry.) “We needed to shoot the same actors and acrobats wearing the same costumes they would be wearing in the live show, so we had to ask the wardrobe and makeup departments to be ready in March for us to begin shooting,” Ranger says. “So the costumes for the main characters had to be finalized by then. That was followed by an intense period of post-production in the last few months, during which I also worked as an editor on different tableaux for the final program, which was completed mostly in Adobe After Effects.”

Ten coolux Pandoras Box media servers were deployed in a dual-redundant configuration, with two Pandoras Box Manager units for real-time show control and synchronization. Fifteen Christie Roadster HD20K-J 3DLP projectors were arrayed in five banks of three to each screen, notes video project manager Nicolas Gendron. (All video, lighting, and sound gear was supplied by Solotech.)

The video program was completed four days prior to the ceremony, but, even then, there was still some rendering to go. “We were lucky that the rendering went according to schedule,” Ranger says. “It could have been a bit tight to render in that format for all the tableaux; also, we were doing about 45 minutes of animated content during the parade of athletes, and we had to create something different for each country. But the most difficult part lay in administering the budget we were given, and trying to figure out how to maximize its value. Once we started production, it all went very smoothly.”

The video team was a small one: two motion designers, an illustrator, a technical director, and Ranger alternating in the roles of designer, video director, and editor.

TRIBUTE TO SOUND

The third tableau began with a short scene entitled Waves, in “homage to Canadian broadcasting pioneer Reginald Fessenden,” says the program notes. To their astonishment, dancers discovered radio waves hovering above their heads as they tumble around an old radio receiver. Snippets of Canadian love songs break through the static, leading to the next tableau, Hearts in Bloom. “The guardian of the long jump chooses this segment for the longest leap of our adolescent lives: the discovery of love. The freedom to choose whom to love is a gift that Canada offers to the world.”

The guardian of the long jump, who also happened to be a sling dancer, performed atop a ring of draped silk, as video of the snow-capped Rocky Mountains taken from a helicopter was projected onto the five screens. Forty dancers from National Ballet School and Toronto Dance Theatre ended up pairing off in various combinations of boy-girl, boy-boy, and girl-girl, to drive the point home.

Providing monitors for hundreds of performers and support staff was a major part of the sound system design. “We were running more than 1,000 in-ear monitors (IEMs), with 20 discrete mixes of Shure PSM 1000 on 60 belt packs, feeding Shure SE425 sound-isolating earphones for the principal actors and singers, and the ten BMX bicycle acrobats,” says Laliberté.

“The remaining 950 acrobats, artists, volunteers, and protocol staff received the program through a new FM system,” he adds. “The most important guys on the gig were the RF people from a new Quebec company, Squelch Inc., and those guys are RF freaks! They built all sorts of custom antennas and cable for us, and they handled all the frequency coordination with Industry Canada, in cooperation with an official from the TO2015 organizing committee. We ended up with four discrete FM mixes: one mix for the 150 kids in the show, without too many distractions and calls in it; a second mix for the adult artists; a third for the volunteers in the parade of athletes and other parts of the show; and a fourth mix for the protocol staff.

“In addition, we were running a few dozen Sennheiser SK 5212-II lav packs and 30 packs of RF intercom,” he says. “The Sennheisers allowed us to change the power on the transmitters, so we could lower the power as much as possible to get as low intermodulation as possible. With this kind of event, our RF has to be integrated into the frequency plan for all the events, because we had to supply a frequency plan to Industry Canada months ago, even before we knew what we were going to be doing. It was a huge undertaking.”

In addition, Laliberté flew 10 Meyer DF-4 long-throw monitor loudspeakers on the acrobatic grid to provide downfill for the aerialists who were not wearing IEMs, and built a shelf around the edge of the stage for 12 Meyer M’elodie cabinets. “I chose the M’elodie because of its very low profile and 100° horizontal coverage; it covered the stage very well,” he says.

Laliberté specified two DiGiCo SD7 dual-engine consoles, one for the front-of-house mix, operated by Mark Vreeken, and one for monitors, mixed by Russell Wilson, and a dual-redundant Optocore signal transport system.

“The show production involved about 90 inputs, with 24 additional inputs from the Riedel Artist intercom system to the monitor desk. Each of the four FM mixes also contained its own interrupt foldback (IFB). While the stage manager, Stefan Miljevic, called the overall show, every specific department had its own show caller. Each dance group heard the dance counts from its own choreographer to keep them in time. Throughout the show, there were different people talking to the children and to the adults.

“We used 48 outputs for monitors only, feeding two Meyer Galileo 616 processors for control,” he says. “The FOH console fed 10 Galileo 616s, and also provided safety mixes to broadcast control. In addition, we sent a MADI stream of all the inputs to Mike Nunan and Anthony Montano who were mixing in the BAS Broadcast Audio Services truck as a backup to their Lawo I/O system.”

Two computers running QLab took care of playback, the second being a redundant backup unit. Analog outputs were used because the Radial SW8 auto-switchers feature only analog I/O. More than 90% of the show’s sound was from playback, the 16 tracks of music arranged as stems to help maintain control of various frequency bands within the venue. Tracks 1 and 2 contained percussion and lowfrequency content, tracks 3 and 4 held the low strings and pads; high strings and pads went to tracks 5 and 6, front sound effects were on tracks 7 and 8, surround music was on tracks 9 and 10, surround sound effects were on tracks 11 and 12, tracks 13 and 14 were reserved for vocals, and tracks 15 and 16 were dedicated to special cues, such as counts, clicks, verbal instructions, and comments.

“The great thing about QLab is that it generates longitudinal time code [SMPTE LTC] in real time. We were still composing until the very last minute, and if we had had pre-recorded tracks of time code, it would have been impossible to deal with—for every change, you’d have to redo the time code track. But by generating time code in real time, we were able to make changes right up to the end. Time code was redundant too, but we’re keeping how we did it a secret! We had a third backup coming from a computer running Digital Performer on a separate power circuit for use if everything else failed.”

The Optocore closed loop ran from a backstage DiGiCo DigiRack, then to a second DigiRack at the front-of-house position. From there, it went to the music playback control room where the show callers, choreographers, producers and three live announcers—French, Spanish, and English—were headquartered, and then back again to the front-of-house console and finally to the monitor console and backstage rack, where the loop was closed. “If we encountered a break on one side, the other end of the loop would still make it,” Laliberté says.

Some 200 EAW stadium house loudspeakers were used as delays. Laliberté took advantage of an additional ring of EAW loudspeakers on the 300 level that are permanently aimed back at the field, pressing them into service for his surround mix with the eight main line arrays of Meyer MILOs flown 70′ above the stage acting as mains.

“When I first went into the Rogers Centre, I was surprised at how good the house PA sounded. So I started the concept from there, using the house system in conjunction with our own. When I saw the first drawings of the stage, I decided to fly eight line arrays so they would be almost equidistant to every seat in the venue, and permit the delay between the production system and house system to be about the same everywhere. Every speaker in the Rogers Centre has a dedicated output from the house [BSS] Soundweb London Blu system, so we were able to fine-tune its 100 zones and delay it to our system. It was really well integrated with our production system,” he says.

While he was able to achieve only 85dB SPL (Cweighted) with good intelligibility in the empty house, Laliberté found that, during the show, with 45,000 human absorbers in the seats eliminating the slapback, he reached almost 100dB with no adverse effects. “It felt like a rock show,” he says.

ROCK SHOW LIGHTING

It also looked like a rock show, thanks to Martin Labrecque’s stunning lighting design, centered on 100 Philips Vari*Lite VL4000 and VL3500 Spots and 109 Clay Paky Sharpys.

“This was the first time I had done something in a stadium,” Labrecque says. “I come from the theatre world, and I do a show with the Cirque about every two years. This was something totally new, and I wanted to get out of my comfort zone. I think the reason they asked me is that they wanted a hybrid between theatre and a rock show. I lit most of the acrobatic numbers with a more theatrical feel, and, between those moments, it’s more like a rock show. The director, Bastien Alexandre, wanted to use the beam of the Sharpys a lot, especially moving in interaction with the Messenger.”

For wash, he used a combination of 80 VL3500 Wash and Wash FX luminaires, together with 30 Sharpys and 24 Martin Professional MAC 600 NTs. “The main grid was an acrobatic grid, so in terms of weight I was very limited, due to all the winches and other equipment used for the aerial acrobatics. So I put most of the Sharpys on the floor around the stage, and used the main acrobatic grid to envelop the artists. We were also aware of the radius of movement when the acrobats were spinning around, and we were careful in positioning the lights to keep them out of the way,” he says, noting that he mounted many of the VL4000s up on the 500 level balcony.

Mathieu Poirier, Labrecque’s associate, notes that the lighting desk setup included two grandMA2 full size consoles (one main and one backup); two grandMA2 light consoles (one for the DP and one for associate lighting designer); and three grandMA2 NPU network processing units.

“Before the load-in, we had about 25 days to build the show on the CAST WYSIWYG and grandMA2 platforms,” Labrecque says. “We had only five nights in the stadium, which is not much at all, and had only three or four hours sleep a night. It was pretty stressful when we saw the first run-through on the morning of the dress rehearsal. That was the first time I saw the show.”

The most difficult part of the lighting design for Labrecque was the requirement to light the show for television as well as for the house. Because his TV experience was limited, he asked Yves Aucoin, lighting designer for Celine Dion, to accompany him during those five nights in the stadium to take care of the television look.

“Yves helped me to build my image so it looked good on the stage and on TV, and we were able to achieve a good balance between the two,” Labrecque says. “Normally, I don’t work with 29 cameras—it’s only my eye. He was incredible. He really helped me to achieve what I had in mind, but for television. He helped me build all the looks so it was really great having him with me. I learned a lot.

“I had maybe five pages of notes that I didn’t do,” he adds. “I just closed my book and said, ‘Let’s hit it.’ There was no time left. We were a team of five: Mathieu Poirier; Eric Belanger, the board operator; Annick Ferland, the followspot operator; Yves Aucoin as DP; and myself. We formed a very tight group. We knew where we were going and they all did a fantastic job. I’m very proud of the team.”

The next two tableaux, A Storm of Possibilities and A Train for Life, were overseen by the gods of wrestling and discus, respectively. The program notes tell us, “Doubt grips us at the moment we begin to choose our destiny. The guardian of wrestling leads young adults into the turmoil of his own inner struggle. They find confidence and strength, and the sky literally rains down professions on them,” in the form of various uniforms and work garb, that they then try on for size in preparation for entering the workforce.

“A Train for Life: Like a thread from coast to coast, the railroad touches territories and people, uniting them, forming a country. It’s the moment of departure from home when young adults leave to forge their own paths. The railroad represents the journey of all athletes who leave home to follow the arduous paths that led them here on this special night. The guardian of discus is here to guide them, help them connect with their individual destinies, inspire them with a shared determination to complete their journeys by building on a strong country and a stable future.”

These two segments featured aerialists performing on spinning ladders, representing the vagaries of upward (and downward) career mobility. A mini-rail train arrived to take them all away, following which 10 BMX stunt cyclists performed death-defying tricks on eight ramps on the floor around the main stage.

MAINTAINING CONTROL

Synchronizing 625 performers and hundreds of support personnel with video and audio playback, lighting, pyrotechnics, hazers, fog machines, motors, and sundry other equipment in a one-time-only live show could easily have become a nightmare. Fortunately, a show-control protocol was established to accommodate any unforeseen changes in pacing and stage management issues.

Each of the different tableaux and the transitions between them began at a different hour of time code. The first tableau started at 01:00:00:00, the next at 02:00:00:00, and so on through the 18 individual sections of the show.

“The LTC from QLab provided ‘go’ commands to the other departments. Video and lighting received their cue, and then they free-ran to their own internal timing reference,” Laliberté explains. “Because of the acrobatics, almost every song ended in a loop, because it was impossible to know in advance precisely when an acrobatic routine would end. So we had to wait for a ‘go’ to proceed with the next song. Every song was produced to be longer than its program length by two or three minutes. Sometimes it would go on to a loop, which obviously doesn’t work with linear time code. Therefore, everybody had to go to free-run and wait for the next cue. Also, with a stage filled with 300 people, you don’t know precisely when it will be cleared, and because of the pyrotechnics and aerials, there were always safety issues. The intercom system was so critical, because we always had to wait for an ‘all-clear’ from the floor managers before we could go on to the next number.

“There were over 400 cues throughout the show. Our playback guy, Martin Ruel, had his finger on the space bar the whole time! The stage manager Stefan Miljevic was the show caller; he had the time code in his head. He was calling the show by reading the time code, and he knew it by heart. It was all manual starts,” he says.

“We used the Riedel intercom system to distribute time code,” Laliberté says. “Every operator’s panel had two audio outputs, so we could supply time code to every position. There were two really big numbers in the show: the opening, and the lighting of the cauldron at the end. In the opening, we also had FSK (frequency shift key) time code that was dedicated to the pyrotechnics. FSK time code has a low baud rate signature, and it can be sent over RF without any problems. That we could not generate, so it was a pre-recorded track that we sent to the pyro team.”

The final tableau, culminating in The Lighting of the Cauldron, began under the watchful eyes of the guardian of running, and involved numerous acrobats running on treadmills high atop scissor lifts, anticipating the torch runners and the ultimate hand-off of the flame to Canadian basketball legend Steve Nash.

Torch in hand, Nash ran out of the stadium, making his way to the cauldron at the base of the CN Tower, where he ignited the cauldron and set the tower ablaze in a dazzling fireworks display that could be seen for miles around, and that rivaled—but could not surpass—the unbelievable show we had just witnessed from Cirque du Soleil.