By ALEXANDRA BERZON and MARK MAREMONT

April 22, 2015 1:25 p.m. ET

THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

LAS VEGAS — Sarah Guillot-Guyard lay dying on the floor of a basement inside a darkened Cirque du Soleil theater here, one leg broken and blood pooling under her head.

It was June 2013, and the 31-year-old mother of two had fallen 94 feet in front of hundreds of horrified spectators after the wire attached to her safety harness shredded while she performed in the dramatic aerial climax of the company’s most technically challenging production, “Kà.”

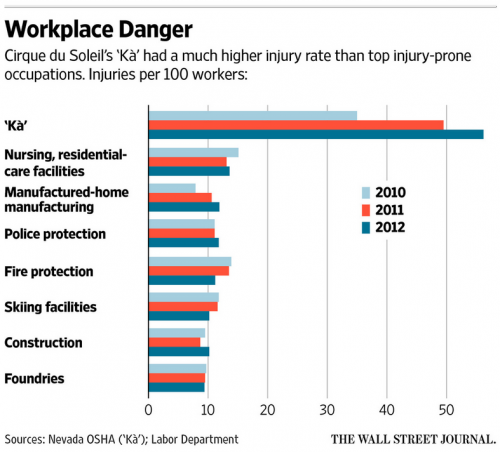

It was the first fatality during a Cirque show, and it capped an increase in injuries at Cirque with the “Kà” production. The show had one of the highest rates of serious injuries of any workplace in the country, according to safety records kept by Cirque that were compared with federal records by The Wall Street Journal.

Montreal-based Cirque, which said Monday that its founder had agreed to sell a controlling stake to an investor group, has evolved from a fringe troupe of avant-garde stilt walkers and clowns into a nearly $1-billion-a-year business. Its 18 shows around the world, including eight resident shows in Las Vegas, combine music, dance and dramatic spectacle with high-wire and acrobatic feats of daring, to dazzle audiences who typically pay $100 or more for tickets.

Cirque is “always trying to push the envelope,” driven in part by Cirque’s own artistic drive, but also by the public “asking for bigger and flashier,” said Bill Sapsis, a theatrical rigging expert in Philadelphia who has worked with it.

The death of Ms. Guillot-Guyard, along with hundreds of injuries among Cirque du Soleil performers, puts in stark relief the question of how much risk is acceptable for the modern, corporate circus, and whether Ms. Guillot-Guyard’s death or some injuries could have been prevented.

Cirque said the incident launched a broad re-evaluation of safety practices at the 30-year-old company, which marketed “Kà” as “extreme,” “terrifying” and “dangerous.”

“It forced us to review the way we work,” said Cirque’s safety director, Nicolas Panet-Raymond.

Multiple efforts to reach Ms. Guillot-Guyard’s family for comment were unsuccessful.

Circuses have long marketed “death-defying” stunts to sell tickets, but experts said that in the modern era the risk-taking is largely an illusion to thrill spectators. Interviews with more than three dozen former and current Cirque employees, along with outside experts, reveal an organization that greatly emphasized safety but also embraced crowd-pleasing feats that stretched the limits of the human body and of theater-rigging technology.

To walk this line, the company provided employees with training and assigned technicians to repeatedly check equipment, trusting that under those conditions the elite acrobats could avoid major accidents, or at least avoid a death when an accident did occur.

SEEMED NERVOUS

But state safety investigators and engineers hired by Cirque found that in the case of Ms. Guillot-Guyard’s death, relying so much on the “human element” of keeping the performers safe—the part that depended on every person doing their job perfectly every single night—could be fatal.

Ms. Guillot-Guyard died during what was only her second live performance of one of the more challenging roles in “Kà,” safety records show. She flubbed her part during the earlier performance that night and seemed nervous to fellow workers. Some questioned her readiness, Nevada state records show.

There had been earlier signs indicating that the safety equation might have gotten out of balance, especially at “Kà,” performed at the MGM Grand casino in Las Vegas since 2004.

The drama features a dizzying array of bodies suspended in the air, sometimes appearing to hurl themselves against a stage that moves between horizontal and vertical planes throughout the show.

That complexity played into the show’s high number of injuries. In 2012, the most recent year for which government data are available, “Kà” had an injury rate of 56.2 per 100 workers—four times that of professional sports teams. “Kà” had 101 full-time-equivalent workers that year. Because industry safety data for circuses are included with other amusement and recreation companies and impossible to break out on their own, safety experts at Cirque said that sports-team records are the most apt comparison.

The show’s workplace injury rates also were more than five times the 2012 rate of some other injury-prone professions—including police work, firefighting, construction and workers at steel foundries. The data come from federal records and internal Cirque documents that became part of a Nevada Occupational Safety and Health Administration report on Ms. Guillot-Guyard’s death that the Journal reviewed in a public records request.

The statistics measure injuries diagnosed by a medical professional, including problems like strains, which make up the majority of Cirque injuries. Cirque records also indicate serious previous accidents at “Kà,” including five falls by aerial performers in the three years leading up to Ms. Guillot-Guyard’s death.

Cirque, which had previously experienced one other performer death in its history, during training in 2009, acknowledges the worrisome comparisons between injury rates on its shows and some other jobs. “We were looking at mining and other professions and saw, wow, our rates are quite high,” said Boris Verkhovsky, director of acrobatics and coaching for Cirque.

But the company commissioned studies using different metrics that showed its performers’ rates in line with some athletes. That gave Cirque more assurance, Mr. Verkhovsky said.

After Ms. Guillot-Guyard’s death, Cirque officials said they realized they needed to do more to engineer safety into the shows. Now, for the first time, Cirque said its managers must incorporate a safety review into every step of designing or modifying any of its shows.

Executives also said they set up a process requiring shows to report accidents that nearly resulted in injuries or fatalities, which triggers an internal investigation into the cause. Previously, the root cause of a serious injury had been investigated but not close calls, executives said. Cirque said there have been no such reports at “Kà” since the change in policy.

Tension over the trade-off between spectacle and safety in circuses has been inherent since trapeze performers began flying 30 feet in the air about 150 years ago. “A circus tent is not an ancient Roman arena or a modern prize ring,” wrote the journal Circus Scrap Book in 1931.

Experts said serious injuries and fatalities can, and should, be prevented with safety harnesses, nets and other protocols, so that, despite the stagecraft, the workplace is safe. “Most of the accidents that have happened in recent times have been preventable,” said Jerry Gorrell, a theater safety consultant in Phoenix.

In the past 15 years, separate from the Cirque death, at least three circus performers—including one at major Cirque competitor Feld Entertainment Inc.’s Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey—have fallen to their deaths during shows in the U.S., according to federal records and company reports.

Cirque, which had its first shows in the 1980s, initially didn’t emphasize aerial acts. The circus’s hits made its owner, Guy Laliberté, a billionaire, thanks in large part to a favorable deal beginning in the 1990s with Las Vegas casinos, which gave Cirque half the revenue of the shows there despite not having to incur costs for the theater, equipment and non-artistic personnel.

The company last year had about $850 million in annual revenue and a staff of about 4,000—1,300 of whom are artists.

On Monday, Mr. Laliberté said he would sell a controlling stake to a group led by U.S. private-equity firm TPG, which declined to comment for this article. Another investor, Fosun Capital Group, is expected to help drive the company’s expansion in China. Terms weren’t disclosed.

“WE’RE A FAMILY”

Mr. Laliberté said in an interview last year that he considered the company “pioneers” in the use of safety harnesses. Cirque requires multiple checks a day on rigging systems and has conservative weight limits for each harness.

“We’re a family,” said Mr. Laliberté. “We don’t want to put our kids in danger. We don’t sell tickets that way.”

Even with safety equipment, there are expected injury risks for Cirque artists, in part because of the punishing demands of a schedule that usually involves performing 10 shows a week.

“Who cannot make a mistake?” said Olena Shaparna, a onetime Ukrainian Olympic gymnast who left Cirque a decade ago after a severe neck injury sustained during a practice session. “If you do those tricks every day, all the time, one day something will happen.”

Some performers said Cirque has failed to take opportunities to improve safety, saying revisions such as mats or nets could make acts safer.

When Cirque’s touring show Kooza was making its debut in Montreal in 2007, safety regulators told the company it needed a net under the Wheel of Death, a long-popular act used in many circuses that involves performers jumping and flipping on top of a giant spinning apparatus. Cirque officials commissioned a net that would be invisible to the audience.

Yet for the same act in the Zarkana show in Las Vegas, Cirque continued to perform the Wheel of Death with no nets. When a performer fell from the wheel in 2013, he missed a mat underneath and slammed into the ground, suffering significant injuries. Cirque safety officials told Nevada OSHA that it didn’t use a net in Zarkana because there isn’t sufficient room due to the way the stage is configured.

Nevada safety regulators found it would be “infeasible” to require more safety systems in the act and cleared Cirque of any responsibility for the accident.

“It is evident that there is a hazardous condition for this line of work and the employee accepts that risk,” a Nevada OSHA inspector wrote.

Cirque declined to comment on all questions about specific performers’ injuries.

The company said this year it hasn’t made significant changes to the Zarkana Wheel of Death and doesn’t plan to. “It’s an apparatus that by definition—even by its very name—is a high-risk apparatus,” said Renée-Claude Ménard, Cirque’s director of communications. The performers “have to be on the ball,” Ms. Ménard said.

Meaghan Muller, a former Cirque performer, said she shattered both wrists, one hand and her jaw in a 2005 fall onto a concrete floor while training in Montreal. “It turned into quite a sour experience,” she said. “I had 13 surgeries, and I walked away with no show and bankrupt.”

Ms. Muller, who believes her injuries would have been less severe had Cirque provided a safety mat during her training, said she remains in pain and can’t do some daily tasks such as cook.

Cirque performers, who aren’t unionized, sign one-year contracts after an initial testing period, with starting salaries around $50,000. Some doing particularly specialized stunts or who play key characters can negotiate higher salaries.

When performers are injured, they file for workers’ compensation, which is standard for most American workers but can result in relatively small payments for injuries that sometimes leave performers with chronic pain or disabilities. Mr. Panet-Raymond, Cirque’s safety director, said, in contrast, some other circus companies treat performers as freelance workers who are offered nothing if injured.

Full data about injuries at Cirque productions aren’t available, but a snapshot of the toll on performers can be seen in Florida, which makes workers’ compensation records public.

Of 61 Cirque acrobats listed in the cast for a 2004 video of La Nouba, a resident Cirque show in Orlando, Fla., 42 were injured seriously enough between 1999 and 2014 to require more than seven lost work days for a single injury, state records show. Of those, 15 performers had five or more such serious injuries, and nine later settled disputes with Cirque and its workers’ compensation insurer, sometimes over career-ending injuries.

In total during those years, 170 Cirque workers in Florida suffered injuries involving more than seven days of lost work, and a few reported a dozen or more such injuries.

“The body is the tool [in the circus], and sometimes the tool gets broken,” said Vladislav Dunaev, a former Cirque performer in Florida. Mr. Dunaev said Cirque had “very good safety measures,” but even so, he suffered seven significant injuries over roughly a decade, state records show, the last a 2011 shoulder injury requiring surgery. In 2012 he reached a $90,000 settlement with Cirque and its insurer after disputing his benefits through an administrative process.

In 2009, Cirque suffered its first fatality when Oleksandr Zhurov, a 24-year-old from Ukraine, died three months into his initial training in Montreal while learning an act on the Russian Swing, a giant two-person contraption that can catapult a performer up to 30 feet in the air.

Mr. Zhurov, who Cirque officials said had previously performed on the swing in other shows, fell backward off the apparatus while performing the less-risky role of the swing’s pusher, hitting his head on the ground with enough force to be fatal, according to a report from Quebec safety regulators.

The Quebec investigators concluded he made a mistake with his foot placement and ruled it an accident. His mother, Larisa, said Cirque treated the family well. “It’s a game of chance,” she said. “One can start crossing a street and never make it.”

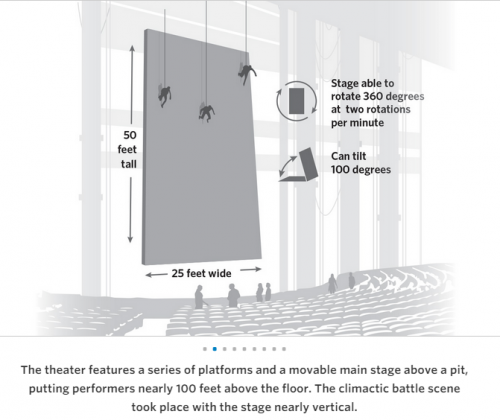

Cirque’s “Kà” show was to be an aerial spectacle on a scale never before attempted, and its marketing highlighted its daredevil stunts.

There would be no fixed stage, just a deep pit where the stage would be. A series of platforms would move back and forth and flip to become fully vertical. Performers would do much of their work as high as 75 feet in the air, with one jumping from 65 feet into an inflated air bag.

“Stuntmen in Hollywood may do a fall like that eight or nine times a year, but our guy does it 465 times,” said Calum Pearson, Cirque’s vice president of resident shows, who was a technical director for “Kà.”

“Kà” is the only Cirque show with a plot. Young twins are separated when one is captured by an evil group. The showdown between the good Forest People and evil Spearmen is the show’s apex. In the battle scene, the two groups perform martial arts and flip against a vertical stage before the Spearmen, defeated, rise out of sight.

A Cirque production coordinator said in a 2005 Cirque marketing video called “Kà Extreme” that the company ordinarily would have backup safety systems, but not in some of the scenes in “Kà.” “If the rigger makes a mistake or the ropes get ripped, there’s no net,” he said.

During pre-production in Montreal, technicians discussed using safety nets as a backup but decided it was unnecessary because the artists are wearing harnesses attached to ropes, a technician later told Nevada OSHA.

Mr. Panet-Raymond, Cirque’s safety director, said safety experts were concerned that having nets underneath might encourage performers and technicians to be less vigilant in using the safety harnesses and could divert resources to staff the nets that would be better used watching the performers.

“The last thing we want to do is create a false sense of security,” Mr. Panet-Raymond said.

Ms. Guillot-Guyard had been trained at a French circus school from a young age, focusing on aerial arts. She joined the show in 2006, and told others to call her “Sasoun” because there was already a Sarah in the cast.

“Sasoun was a tank,” said Marc-Antoine Picard, a Cirque artist who was performing near Ms. Guillot-Guyard just before she died. “She was going somewhere and you better not get in her way.”

CATWALK DANGER

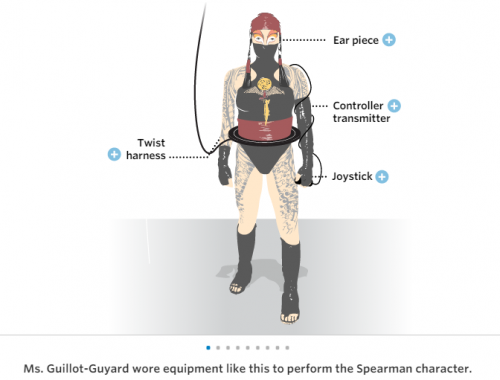

Ms. Guillot-Guyard played several roles in “Kà,” but after her part in the battle scene was eliminated due to company-wide budget cuts, she begged to learn the role of a Spearman, a technically challenging role normally played by men, according to Mr. Pearson. She began training in April 2013.

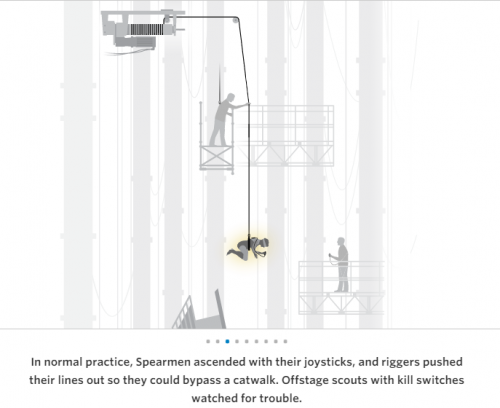

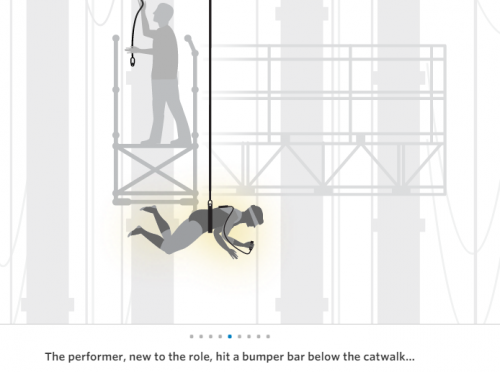

Well before then, Cirque had experienced trouble with the role. As they flew up and out of the scene after being defeated, some of the Spearmen would hit the bottom of the catwalk they were supposed to exit from, sometimes getting injured. They controlled their own speeds with a joystick, going as fast as 11 feet a second.

Cirque officials added technicians watching the lines down below who were supposed to hit an emergency switch if they spotted trouble. Technicians called riggers stationed above were instructed to lean over a railing on the catwalk and push the performers’ lines away as they rose to help them avoid colliding with the structure.

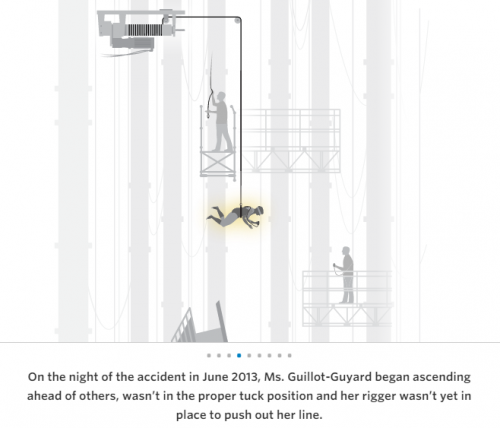

There were two shows scheduled on Ms. Guillot-Guyard’s inaugural night in her new role. Riggers, coaches and other performers later told Nevada OSHA that she had said she was nervous and had expressed insecurity. During the first show of the night, she had trouble initially clipping her harness, which delayed the scene by a few seconds, and at the end of the scene rose slowly and jerkily, and needed help from her rigger to climb onto the catwalk, they said.

In between shows, as staffers relaxed playing table tennis, her rigger told others she “needed more work on the fly-outs,” according to his statement to OSHA investigators. “I didn’t think she was ready,” he said.

Disaster struck at the end of the second show. When the Spearmen lined up to fly out backward, Ms. Guillot-Guyard was already 8 feet above the others when she should have been even with them, witnesses said. Using her joystick, she seemed to rise faster than normal, according to the OSHA report.

Her rigger was still working on clipping his own harness into his safety line, so he didn’t push out her line as he was supposed to do, according to the OSHA report and Cirque officials.

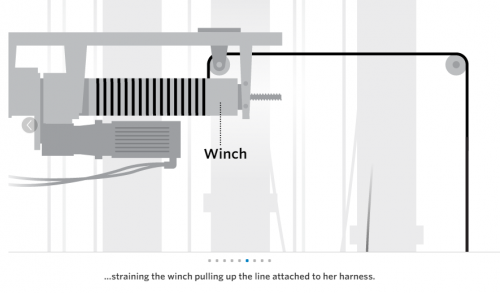

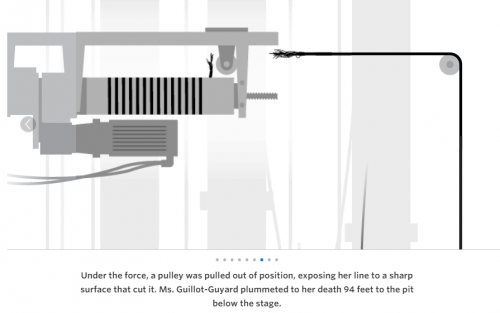

Ms. Guillot-Guyard slammed against the catwalk, causing the safety wire to come out of its pulley and scrape against a sharp edge, ripping apart. The aerialist plummeted the equivalent of about nine stories to a lower basement and landed on her back.

“I wasn’t there,” her sobbing rigger later told a fellow employee, according to OSHA records. “I felt the rope go through my hand.”

The company, in its own investigation, concluded that its safety protocols had relied too much on performers’ and technicians’ actions rather than on engineering systems, officials said.

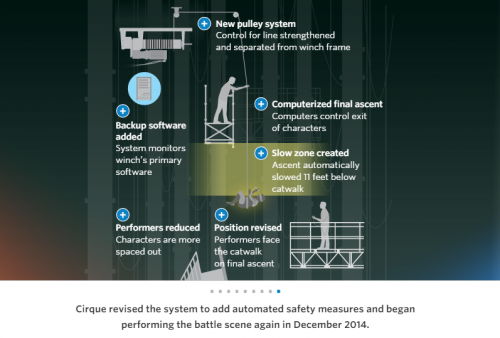

Cirque stopped performing the battle scene after the accident but recently restored it after revising choreography and installing new safety systems that it said cost $500,000.

The company now uses technology to prevent performers from approaching the catwalk too quickly, has reduced the number of characters to give them more space and has performers face upward on the final exit. It replaced the pulley system that failed with one clamped to the ceiling and added a backup software system to monitor the winch’s primary software.

After investigating Ms. Guillot-Guyard’s death, OSHA issued three serious citations to Cirque, saying among other things that the performer wasn’t properly trained, and fined the company $21,000. Cirque protested, and two of the citations were removed and the fine was reduced to $7,000.

Nevada court records show Cirque settled a legal complaint by paying Ms. Guillot-Guyard’s children, now 7 and 10 years old, a total of $1 million.

—Lisa Schwartz contributed to this article.

{ SOURCE: Wall Street Journal | http://goo.gl/7ArXkY }