It wouldn’t be summer without the circus – specifically Cirque du Soleil, who are back on stages after an absence of 15 months. Because of the pandemic, the internationally-acclaimed company was forced to close over 40 productions – including several resident shows in Las Vegas – and let go more than 95 per cent of its staff. They even filed for bankruptcy protection last year, selling the company to some of its creditors (Catalyst Capital Group) last November.

Now, Cirque is flipping back into action, complete with a savvy marketing campaign that includes a tear-inducing video called Intermission Is Over, featuring Cirque performers finishing up their temporary jobs (in variety stores, empty offices, cafés) and going back to the big top.

The company, still based in Montreal, has reopened or is about to reopen several of its resident Las Vegas shows. The family-friendly Mystère is back in action at Treasure Island, while the water-based show O is currently making a splash at the Bellagio. Michael Jackson ONE at Mandalay Bay is set to reopen August 19, and The Beatles LOVE at the Mirage on August 26.

The company’s show Kooza will return to Montreal’s Old Port in April 2022.

Here in Toronto we’re not quite ready for indoor theatre yet – we’re gradually getting used to outdoor performances.

But with the return of Cirque on the international stage, I thought it would be fascinating to revisit NOW’s cover story from July 1988, back when the company was on its first North American tour. Cool fact: Cirque began as a street theatre company called Club des Talons Hauts – or the High-Heels Club, a reference to stilt-walking.

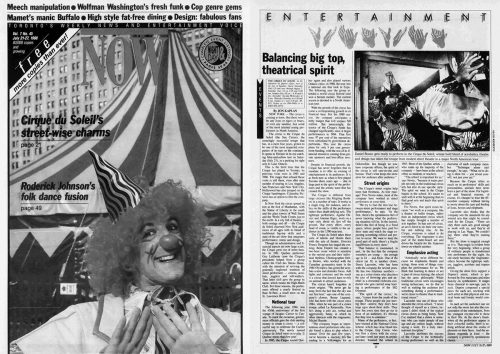

Senior theatre writer Jon Kaplan went down to see the unnamed show (the first named show would come in 1992 with Saltimbanco) at the foot of New York City before its Toronto run. The World Trade Center was just north of the venue. He talked to clowns Benny Legrand and Denis Lacombe (who adorned the cover, in a shot by photographer Algis Kemezys) and tour manager Yves Neveu.

They discussed the company’s humble roots in street theatre, the funding model for the company – in 1984, its first year, 97 per cent of its operating budget came from government funding, while in 1998, only 5 per cent did – and the importance of the National Circus School.

One of the things that distinguished Cirque from other circus companies was the fact that it didn’t use animal acts – something that made financial sense at the start. It was cheaper to tour some 85 people without also worrying about caring for and feeding lions and elephants.

Clown Lacombe also said if they were ever to use animal acts the only ones of high enough quality were based in Las Vegas, and they wouldn’t be able to pay them what they were making there.

Little did he realize that, five stratospheric years later, Cirque would take up residency in Vegas itself with Mystère, the first of many custom built shows to come.

Fittingly, it was the first Cirque show back on the strip.

Below is Jon Kaplan’s cover story, Cirque du Soleil’s street-wise charm, republished from the July 21, 1988 issue of NOW.

BALANCING BIG TOP, THEATRICAL SPIRIT

By Jon Kaplan

NEW YORK CITY – The circus is coming to town. But there won’t be any lions or tigers or bears, or even any sawdust. Just some of the most talented young performers in North America.

The circus is the Cirque du Soleil (the Sun Circus), the amazingly successful troupe that has, in a mere four years, grown to be one of the most respected companies of its type on the continent. It opens in Toronto in its eye-catching blue-and-yellow tent on Saturday (July 23), in a parking lot right next to Lake Ontario.

This is the third time that the Cirque has played in Toronto; its previous visits were in 1985 and 1986. The magic that infused those visits is still there, even after nine months of touring in Los Angeles, San Francisco and New York City. Hollywood has also jumped on the Cirque bandwagon; Columbia Pictures has an option to film the company.

In New York the circus spread its tent at the foot of Manhattan, with the Statue of Liberty to the south and the glass towers of Wall Street and the World Trade Centre just to the north. In a city full of theatre – both onstage and off – the Cirque du Soleil charmed New York audiences of all ages with its blend of traditional big-top skills and a state-of-the-art show that integrates performance, music and design.

Though its administrative and financial aspects are now large-scale, the Cirque grew out of street theatre. In 1981, Quebec performer Guy Laliberté (now the Cirque’s president) helped form a group called the Club des Talons Hauts, with the intention of reviving the generally neglected tradition of street performers – clowns, acrobats, jugglers and stilt-walkers. That latter skill gave the group its name, which means the High-Heels Club. For three seasons, the performers offered a yearly festival in Baie St-Paul, a small town on the St. Lawrence River.

NATIONAL TOUR

The following year, 1984, was the 450th anniversary of the first voyage of Jacques Cartier to Canada. To mark the occasion, government officials gave the club starting money to create a circus – a colourful way to celebrate the Cartier anniversary. The newly named Cirque du Soleil went on to play 11 Quebec towns that first year.

In 1985, the Cirque toured Quebec again and also played various Ontario cities; in 1986, the tour was a national one that took in Expo. The following year the group attended a world circus festival (and won a bronze medal). The current season is devoted to a North American tour.

With the growth of the circus has come a corresponding growth in its financial base. For the 1988 season, the company anticipates a hefty budget that will surpass $10 million. But interestingly, the source of the Cirque’s funds has changed significantly since it began performances in 1984. That first year, 97 per cent of the operations were subsidized by government departments. This year the circus plans for only 5 per cent government funding, with the rest of its financial resources coming from private sponsors and box-office revenues.

Despite its financial growth, the Cirque has never forgotten that its mandate is to offer an evening of entertainment to its audiences. It is as fresh now as when it first played Toronto three years ago – due in large part to the spirit of the performers and the artistic team that has created the show.

The Cirque is different from large circuses like Ringling Brothers in a number of ways. It works in a single ring, for instance, and relies on the skills of the performers rather than death-defying acts. The tightrope performers, Agathe Olivier and Antoine Rigot, work on a rope only about six feet off the ground. But every effort, every bead of sweat, is visible to the audience in the 1,700-seat tent.

The Cirque du Soleil takes these sorts of talents and blends them with the arts of theatre. Director Franco Dragone has staged the evening; Rene Dupere has created a two-hour score which is sensitive to the various acts and their individual rhythms. Choreographer Debra Brown, who worked with the Canadian gymnastics team in the 1984 Olympics, has given the acrobats a new and dramatic focus. Add lights and costumes and the result is a circus that doesn’t have to rely on animals to attract audiences.

The circus hasn’t forgotten its street origins. “We never get far away from the fact that the sky was our first tent,” says one of the company’s clowns, Benny Legrand, who has been with the circus since 1984, when he was part of a clown troupe called La Ratatouille. Now he’s doing a solo act, verbal and aggressively funny, in which he often interacts with the ringmaster, Michel Barette.

“The company began as unpretentious street performers who simply found a place to play when it rained. Over the past five years, we’ve become a success; it’s like trading in a Volkswagen for an Oldsmobile. But though we now have corporate offices, the spirit of the circus is still one-on-one and human. That’s what keeps the show alive for audience after audience.”

STREET ORIGINS

The Cirque’s street origins help keep that freshness. As tour manager Yves Neveu notes, most of the company have worked as street performers at some time.

“We try to find the thin line between street performance and stage performance,” he says. “In the first, there’s the spontaneous feel of never knowing what the performing situation will be. In the second, there’s the feel of being in a fixed space, where people have paid for their seats and watch the stage expecting something refined and precise to occur. We want to keep the good part of each; there’s a fragile equilibrium in every show.”

That balance is maintained, in part, by the fact that the company members are young – the average age is 24 – and fresh. One of the eldest (at 31) is another clown, Denis Lacombe, who has been with the company for several years. He has two hilarious numbers – one as a robot clown who discovers the joys of throwing pies and another as a demented orchestra conductor who gets carried away leading a performance of the 1812 Overture.

“The spirit of the circus,” he says, “comes from the youth of the troupe. These people are just starting their careers; they don’t have large egos about their skills. They have fun every time they go out in front of an audience; it’s obvious that they love to entertain.”

Many of the performers, in fact, have trained at the National Circus School, which has close blood ties to the Cirque. Guy Caron, who was first a clown with the circus and later (until last year) its artistic director, founded the school in 1983. Most of the Quebec artists – who make up the majority of the company – have been at the school either as students or teachers.

“The school is important for us,” says Neveu, “because it trains people not only in the traditional circus arts but also in our specific style. The spirit we want in the Cirque begins in the school. It’s easier to start with it at the beginning than to find good acts and teach that spirit to them.”

For Neveu, that spirit exists because “we work as a company, like a theatre or ballet troupe, rather than an independent circus which has simply brought a number of acts together. In that sort of circus, an act is hired to do their one number and nothing else. At the Cirque, everyone is asked to do everything. The ringmaster is also part of the teeter-board act and drives the bicycle for the 11-person tower-on-wheels number.

EMPHASIZE ACTING

“Artistically we’re different because we emphasize theatre and acting; those sorts of things complete the performance for us. We think that learning to dance or act is part of circus training; the school has the same philosophy. While traditional circus work encourages strong technicians, we do that as well as making the audience feel something during a performance; we’re closer to theatre than to traditional circus.”

Lacombe was one of those who attended the circus school. “I never thought of myself as a clown, because I didn’t think of the typical circus clown as being funny. Now I’ve realized that a clown is someone who can make people of any age and any culture laugh, without saying a word. It’s a truly international discipline.”

Lacombe attributes the success of the Cirque to the technically strong performers as well as the charisma of each company member. “Technique alone isn’t enough,” he says. “What we’re doing is show biz – you reveal yourself, not just your act.”

Because the Cirque relies so much on its performers’ skills and personalities, animals have never been a part of the show. For logistical and financial reasons, of course, it’s cheaper to tour the 85-member company without having to worry about the care and feeding of lions, horses and elephants.

Lacombe also thinks that the company sets the standards for any animal acts that might be considered for the Cirque. “There are only three such acts good enough to work with us, and they’re all playing in Las Vegas. We couldn’t pay them what they’re making there.”

But the show is magical enough as it is. That magic is evident from the very beginning, when a group of ordinary people is transformed into performers for the night. An old uncle becomes the ringmaster; others become the tightrope walkers, jugglers, acrobats and trapeze artists.

Giving the show firm support is Dupere’s music, which is performed by five musicians and relies heavily on synthesizers. It ranges from classical to new-age, jazz to rock. Dupere composed a special piece for each act, working with each artist so that physical and musical beats and breaks would coincide.

In each act the audience can see not only the sweat but also the concentration of the entertainers, from the youngest six-year-old to those in their 30s. At the show’s finale, when all the performers appear in their colourful outfits, there is nothing artificial about the smiles of pleasure on their faces. And the audience responds in kind – the company is greeted by spontaneous cheers.

{ SOURCE: Now Magazine, Toronto }