Inside Cirque Du Soleil Founder Guy Laliberté’s Plan To Create Another Entertainment Phenomenon

By: Madeline Berg, for FORBES Magazine

Guy Laliberté stands on a dock at the old port of Montreal and surveys the skyline. This is the city of a hundred steeples, as well as the 20-story La Grande Roue de Montréal Ferris wheel and the 90-year-old Jacques Cartier Bridge, its cantilevers a bright aqua blue. Up above is Mount Royal, the hill topped with a 100-foot steel cross. To his right, a blue-and-white-striped circus tent.

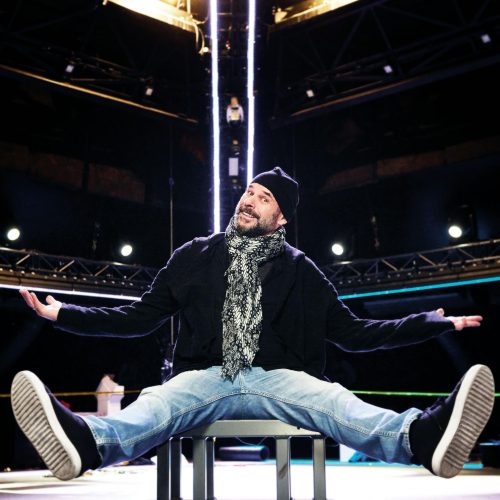

“My first baby,” says Laliberté, pointing to the big top, where Cirque du Soleil performs. A black beanie is pulled over his head, a pair of ripped jeans hang on his hips. Laliberté turns to the left, where an 81-foot-tall gleaming white pyramid stands. “My new baby,” says Laliberté, 59.

The pharaonic structure, formally known as PYI, spans 15,000 square feet, cost $30 million and is now home to Laliberté’s new acts. During the day it hosts “Through the Echoes,” an immersive light and sound show. It’s as trippy as it seems—and it only gets more so at night, when DJs arrive to spin into the early hours of the morning, presenting themed sets like “Candy World,” “Astral Plane” and “Sci-Matic.” Attendees to these events are encouraged to incorporate the evening’s theme into their attire. In “Candy World,” for example, partiers dress in shades of fluorescent pastels, creating visions of acid-laced sugar plum fairies. “Be cute, be evil, be twisted,” the event’s advertising tagline instructs. “Be anything you’d like—just don’t be shy about it.”

This is Laliberté unleashed and uninhibited once again. Decades ago, he poured those impulses into Cirque du Soleil, creating one of the most profitable and famous pieces of performance art of the last century. Most recently, it has become a franchise. There is Cirque, the Michael Jackson version. Cirque meets Messi. Cirque does the Beatles. Cirque goes underwater. It was all very lucrative—and, after a while, replicative with a predictability bordering on boring.

The Billionaire Behind Cirque Du Soleil Debuts Montreal’s PY1 Pyramid

Laliberté wanted to do something else, so in 2015, he sold off most of Cirque—walking away with $1.5 billion to put into new endeavors. Some of that went to more real estate, a family office, some startup investing and art purchases, too. And then, two years ago, he launched Lune Rouge Entertainment, the corporate parent company of the pyramid and the psychedelic shows within it. Lune Rouge is not where most of the proceeds from Cirque’s sale went—he has probably sunk about $100 million into it between constructing the pyramid and developing the live entertainment—but it’s certainly the most visible part of his second act. And given how Cirque turned out, it could very well turn out to be more valuable than anything he has done since Cirque.

“He’s a winner. His name is associated with winning. You know it will work,” says Yves Lalumière, CEO of the Tourisme Montréal. “People will want to follow him without even knowing where he is going—you know he will deliver.”

What’s happening in Montreal is only the beginning. The pyramid opened there in June and will close in September. It will be taken down and moved to Miami this fall and then possibly to New York. Laliberté is not shy about his ambitions. “A pyramid,” he says, “in every city.”

Laliberté sees himself as made up of two halves: performer and capitalist. The fusion of those two occurred long ago. “I grew up in this type of very balanced world of business and creativity. My mom was very, very creative, eccentric. And my father was a PR guy, a wheeler-dealer,” he says from the red leather driver’s seat of his Range Rover as he maneuvers through downtown Montreal. “I really believe that one gift my life have given me is this fifty-fifty creative-business brain.”

In 1978, he dropped out of college to become a busker, playing an accordion he’d found in his father’s closet.?He left his hometown the next year and hitchhiked through Europe. There he perfected his craft, learning skills like stilt-walking and fire-breathing. A few years later he returned home and joined a professional troupe called Les Échassiers—“stilt-walkers” in French—in Baie-Saint-Paul, a Canadian town off the St. Lawrence River. Still partly the kid who sold baseball cards in his schoolyard at age 5, he became one of the group’s leaders, organizing shows and raising money.

Les Échassiers hit it big in 1987 when Quebec offered the group $1 million to create a circus-themed traveling performance for the 450th anniversary of Canada’s discovery. “We had every problem starting a big top could have,” Laliberté told Forbes in 2004. “The tent fell down the first day. We had problems getting people into the shows. It was only with the courage and arrogance of youth that we survived.”

But they ended up turning a $40,000 profit and soon streamlined the performance. With the help of government grants and loans, the show added fanciful costumes, gravity-defying acrobats and emotional music. Cirque du Soleil was born.

“I remember at the opening of our show my mom realized that this was a serious thing that we were doing,” he says. Grinning, he adds, “With my father, it took, like, two more years.”

Cirque du Soleil expanded, betting everything it had on a show called Cirque Réinventé—the story of normal people entering a mystical alternate reality where they join a circus—that premiered at the Los Angeles Arts Festival. It was a gamble: Laliberté and company had only enough money for one-way tickets to California. If they failed, they’d be hitchhiking back to Canada.

In the end, they could’ve flown home first class. Cirque Réinventé sold out throughout southern California before traveling the globe for three years. In 1993 the Treasure Island Hotel opened in Las Vegas with a theater dedicated to Cirque du Soleil. The next year Cirque’s revenues hit $30 million. Two years later, they were $110 million. By the early 2000s, the circus was putting on five different shows a night in Sin City and had permanent spots in Disney World, China and Japan. Sponsors like American Express and AT&T lined up to partner with the upscale acts, while merchandise like teapots and leather jackets brought in millions.

When Laliberté sold Cirque in 2015, 10 million people were seeing its shows each year. Cirque employed 4,000 people—more than, say, Airbnb or Hasbro—and brought in $845 million in revenue.

The scale was huge, the acts were repetitive and Laliberté was growing tired. He tried to find a buyer in Montreal but ended up making a deal with TPG Capital, a San Francisco private equity firm. In 2015, he sold the bulk of Cirque, keeping 10% of the company and the right to be involved in Cirque’s creative decisions. What next? “I gave myself an objective: I really was missing performing as an artist. When I started Cirque, I pretty much gave up performing. It’s really something that I wanted to live again,” he says.

The sale left him with a great deal of money—and a great deal of time to think about what he wanted to do. Laliberté bought hundreds of millions in real estate—a French Polynesian island, a 270,000-square-foot complex of seven Montreal office buildings—and bought works by the likes of conceptual artist Jenny Holzer. He parked some money in green startups such as FoodHero and some in digital marketing companies like HelloStrategy. (He declined to give details on specifics investments.)

But he longed to do something truly creative. He thought about going professional with his DJing hobby. In November 2016, he played his first paid gig in New York. He won’t say where he performed—to save the club’s reputation, he insists. Because when he went to cash the $4,000 paycheck from the performance, the check bounced.

“It really brought me back to my street-performer days,” he says from behind a haze of Gauloises Blondes cigarette smoke. “There’s no way those people were getting away with not paying me.”

Okay. Maybe not DJing. Laliberté thought about it a little longer, pondering how to create another Cirque-type spectacle that would take advantage of the significant advancements in technology since Cirque’s creation. Whatever he built, he wanted it to be able to morph as he thought more about what could work. “I wanted to create a sandbox to grow creatively for the next ten, fifteen years,” he says.

What would that sandbox look like? For centuries, dome-shaped venues have been the preferred spaces for immersive technology. That seemed too obvious. “We wanted to do it in a shape that is different,” he says, an espresso now in his hands. His mind went to the pyramids, a spiritual symbol revered around the world.

Unlike the Egyptian pyramids, which entomb the dead, Laliberté’s pyramid courses with life. The theater is equipped with massive screens, 126 speakers, 32 projectors, 948 lights and 39 lasers. There’s a smoke machine, too, and a bubble machine. Its first show, “Through the Echoes” is itself a celebration of life. The hour-long performance tells the story of the Earth’s creation from the Big Bang to the rise of mankind. Laliberté calls it a “technological and emotional odyssey.” “It’s very reminiscent of when I first started with Cirque,” says Michael Anderson, the pyramid’s production director, who began working with Cirque du Soleil in the mid-1990s. “Only today we have more money.”

“Through the Echoes” is a loosely told narrative, and audience members experience it by lying on the floor, heads on pillows. Visually it feels like being inside a lava lamp. Laser beams flash, and organic, abstract images project onto all four sides of the pyramid. In one moment the pyramid seems to be transformed into the Milky Way. In another it’s lit up in flames before becoming a futuristic garden. The soundtrack—at some moments soft, in others, intense—matches the images.

“I always want to create things that have not been done,” Laliberté says. “The pyramid … will be what the blue-and-yellow big top was for Cirque du Soleil.”

Each pyramid is expected sell about 200,000 tickets (for $21 to $45 each) during a show’s three-month run just for the daytime performances. The DJ-led events—on Thursdays, Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays—can bring far more, perhaps tens of thousands of dollars each night. Laliberté imagines the space as a home for fitness, yoga or meditation classes in the morning, and shows there should be less costly to put on than Cirque with its many performers and, in the case of the Michael Jackson circus show, royalty fees. Meanwhile, another part of Lune Rouge, the pyramid’s parent company, is figuring out how to turn the ideas behind the shows at the pyramid into other media—everything from comic books and podcasts to video games and TV shows.

“I’m not stupid. I evaluate danger, but I trust life is good,” says Laliberté, taking a long drag on his Gauloises. “And I trust that there’s intelligence behind a decision we’re making, and if you want to be a game-changer, you just have to take risks.”

https://www.forbes.com/sites/maddieberg/2019/08/13/guy-laliberte-cirque-du-soleil-py1-lune-rouge/#3a8d3d8a5fdc